In contemplating the challenge of helping the National Park Service achieve its goal and role in preserving the cultural history of Isle Royale, my thoughts return to the question of why. It’s a question I posed in a post in 2022:

Why restore a 115-year-old lighthouse…in the first place? Whom does it serve? The National Park Service? Why? The volunteers who make it happen? That’s a pretty small group in the end. Visitors to the park? That starts to make some sense. But what is the endgame?

In search of insight, I took advantage of a recent horse camping trip to observe how historic preservation from a similar era can take shape in an entirely different setting.

Fort Robinson, located in the northwestern part of Nebraska, was established in 1874 as a temporary encampment during the Indian Wars and eventually evolved into one of the largest military installations on the Northern Plains. After serving as a regimental headquarters for the Army cavalry, a quartermaster remount depot (horse processing center), and a training center for pack mules and K-9 dogs during World War II, it was abandoned in 1948 and turned over to the USDA as a beef research station.

When the beef operation was phased out in the 1970s, the entire military reservation was transferred to the state of Nebraska for public use. Now 22,000 acres in size and part of the Fort Robinson and Red Cloud Agency historic district, it’s managed by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. We benefited from that transition by riding on a few of the many miles of trails on horseback.

Walking through the Fort, I saw lots of historic enlisted and officers’ housing, several large headquarters buildings, horse stables, and service buildings (including a veterinary hospital, shops, and storehouses). It’s estimated that over 65 of these buildings are more than 100 years old. And all look well restored and maintained. Most of the officers’ quarters are rented to visitors, while some are occupied by employees and volunteers.

Two museums interpret the past at Fort Robinson—one focuses on the fort’s own military history, while the other is a natural history museum operated by the University of Nebraska. The latter, located in a former Army theater, is anchored by a dramatic centerpiece: the remains of two Columbian mammoths that perished in combat nearly 10,000 years ago. Their fossilized skulls, tusks still interlocked, were unearthed just 13 miles from the fort by a 21-year-old University of Nebraska senior, who led the excavation that revealed first one skull, then the other. Certainly something you wouldn’t expect to see in a state park hundreds of miles from the nearest city.

Another display I toured - one side of a duplex officers’ quarters, dating to the late 19th century - has been restored by the Nebraska State Historical Society to reflect the life of a typical Fort Robinson officer and his family. Stepping through the front door, I entered a wide, elongated hallway designed to both welcome guests and showcase the family’s treasured possessions. Along one wall, a doorway opened onto a plexiglass-protected view of the living room and, beyond it, the master bedroom—arranged much as they would have appeared more than 150 years ago. Another doorway revealed the dining room, followed in sequence by the kitchen and, tucked behind it, the servants’ quarters.

The fort had a reputation as a bit of a military country club by comparison to other installations, and I could see why. Standing there, it was easy to picture Mother coming in from playing the pedal piano and the children coming in from their rooms, with the family gathering around the dining table as food was served from a wood stove in the summer heat. Their servant was usually an unmarried young girl seeking a start in life, with more space and many more comforts of home than I would have imagined on the post-Civil War frontier.

Living history, they call it. The chance to step into an era when life was far less comfortable and leisure was rare. It provides some spectrum against which to compare today’s notions of “hardship” and “suffering”. In an age when the visual increasingly shapes how we think and understand the world (think online videos and vlogs), examining the past through this analog lens can reveal a contrast that deepens our sense of context - something that seems increasingly lacking in our educational institutions.

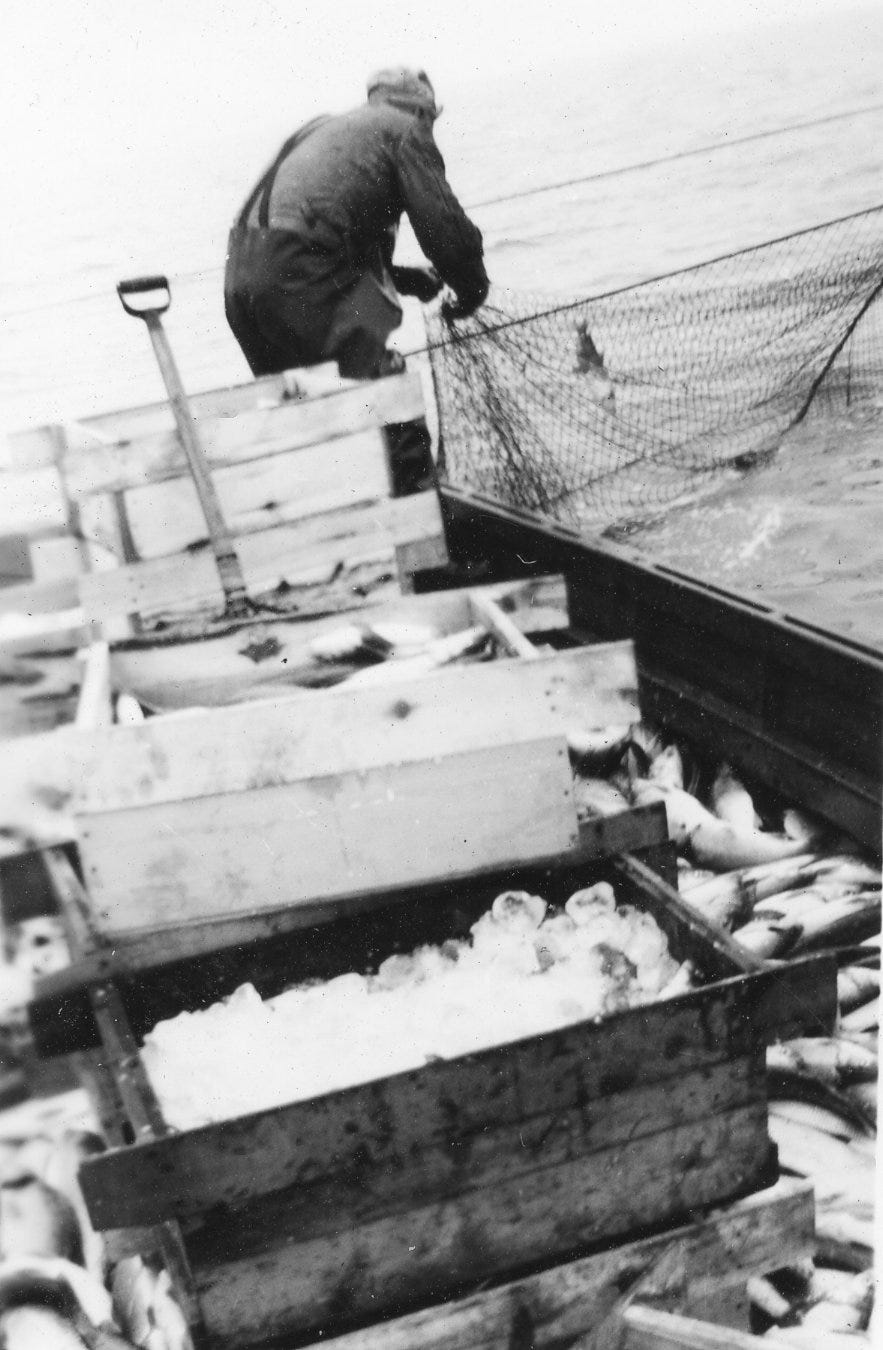

Nebraska has invested in restoring and preserving that history for the future, so future generations can step into its echoes and recognize their place in it, and perhaps gain a deeper appreciation for how far we have come. I’m wondering how we might do the same with the fishing, mining, maritime, and resort history of Isle Royale. More on that in coming posts.

Comments

Post a Comment