This is the third in a series of posts about the future of the Rock of Ages Lighthouse and the proposal to restore and preserve the other historical sites in Isle Royale’s Washington Harbor.

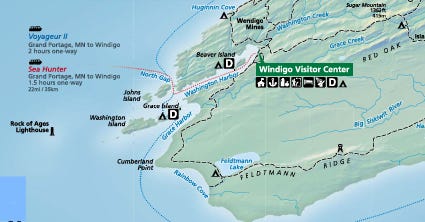

I’ve made many trips to the Rock of Ages Lighthouse in my role as boat operator for the Rock of Ages Lighthouse Preservation Society (ROALPS). My job is to transport crew and supplies from the Windigo dock to the Barnum Island base station, then out to the lighthouse and back again. It’s work I genuinely enjoy, not only for the people, the history, and the stunning environment, but also for the challenges it presents. And it can be a real challenge.

Not the leg from the ferry dock to Barnum Island—that stretch runs over well-protected water, calm in almost any weather. But from Barnum to the Rock is another matter entirely. Conditions must be calm, and the seas relatively flat, to make that passage safely. A significant portion of the time, I decide not to go—either because of current weather or residual swell from storms a day or two before. It’s also not uncommon for the water to look fine from the dock at Barnum, only to discover once outside the shelter of Washington Harbor that the wind-driven swells make the approach to what remains of the lighthouse dock too dangerous. And yet, on those occasions when I go anyway—because we need to get the crew off the Rock in time for the ferry, or a weather delay has already eaten into their limited work window, I can’t help but enjoy the challenge.

Enjoy might not be the right word. Maybe it’s the feeling of accomplishment when I’m successful and the crew is on station, or back in the safety of the Barnum cabin. Or maybe it’s the rush of adrenaline that comes over me at the moment an unintended maneuver forced by wind, current, or wave takes us too close to the surrounding reefs or the submerged wreckage of part of the deteriorated dock. To this day, however, we’ve had no incident of lasting damage to the boat or, more importantly, any threat to passenger safety as a result of the increased risk. Perhaps it’s the relief of escaping the potential consequences of accepting that risk that feels rewarding.

All of that to say that if someone, say an important donor to the effort, were to visit on a given day with the expectation of taking a tour of the lighthouse, chances are good that they’d be disappointed by the failure to actually get there. Similarly, any day-tripper who booked a tour months in advance, on the promise of a unique experience, would also be disappointed.

If a large percentage of potential visitors leave disappointed by their inability to access the light on a given day, it won’t take long for word to get out, presumably leaving the demand for visits dependent on those already at the dock who happen to have an interest on the day they win the weather lottery.

Reliable accessibility is one of the necessary ingredients to a successful vision of attracting and entertaining visitors with a historical tour of the light. Reliability is driven by two things: the condition of the dock and the availability of transportation.

The U.S. Coast Guard constructed the dock, which currently has a landing zone of approximately 22 feet, but is missing around 20 feet of its original length. That is now underwater and poses an underwater hazard due to deterioration from ice and storm damage. Rebuilding this dock requires remote construction equipment and floating platforms, all of which are vulnerable to the whims of Lake Superior’s weather. In short, it’s an expensive undertaking—one that will be difficult for the National Park Service to fund within its current budget, especially in these uncertain times.

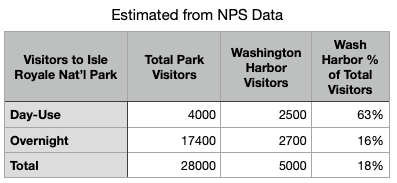

The lack of transportation also limits access to the lighthouse. On the opposite end of the park, at Rock Harbor, a concessionaire operates the MV Sandy tour service to the Passage Island Lighthouse. That area supports such service thanks to higher visitor volume—about 80 percent of all park visits originate there, and most visitors stay for several days. In contrast, only about 20 percent of visitors enter from the Minnesota side, where lower use has led to less infrastructure, staffing, and concession services.

Consequently, economic viability becomes a key ingredient, which depends on having enough passengers and charging a fare that makes the service sustainable. Examining recent visitor data from the NPS, we can estimate potential demand based on the assumption that day-trippers constitute the most likely market.

More than half of the approximately 5,000 visitors who arrive from Grand Portage are day-trippers. It’s a potentially favorable market profile, but the numbers remain too small to justify a major investment in transportation. Even if most of those 2,500 day-trippers chose to extend their visit to the lighthouse, and weather conditions fully cooperated, the volume would still fall short of supporting the necessary transportation investment. A well-coordinated marketing campaign—or exceptionally strong word of mouth—could help boost visitation. Still, any significant increase would also require the Park Service to expand staffing and permit ferry operators to add capacity and sailings. Those are not inconsequential commitments.

Another factor in the equation is the park’s evolving relationship with tourism. As I noted in my previous post, the perception of day-trippers and the broader notion of “tourism” often conflict with the wilderness ethic held by many Isle Royale users and wilderness advocacy organizations. Tourists are sometimes seen as diluting the island’s sense of solitude and wilderness character—a tension the Park must continue to navigate carefully.

Fortunately, much of the Washington Harbor area is deemed non-wilderness. In the National Park Service’s own Cultural Management Plan for the non-wilderness area of Isle Royale, it calls for:

Emphasis on restoring cultural landscapes and providing additional visitor opportunities, and,

Infrastructure additions and adaptive reuse of historic structures and cultural landscapes on Barnum and Washington Islands.

This bodes well for the possibility of increasing visitation and achieving a critical mass for allocating infrastructure and staffing to support these activities.

The third—and likely not the final—ingredient in realizing ROALPS’s vision for the lighthouse is funding capacity. Whether it comes from the government through NPS capital project allocations, or from private and nonprofit sources for operations and restoration, the scale of investment required far exceeds what any current partner can sustain. From dock reconstruction to transportation infrastructure and contractor-led restoration work, the path forward represents a financial mountain yet to be climbed.

In the next post, I will discuss some of the ways we might be able to address these challenges.

Comments

Post a Comment